John Chamberlain

P.H.I.P

P.H.I.P

1979 Painted steel 67.5 x 75 x 64 cm / 26 5/8 x 29 1/2 x 25 1/4 in

John Chamberlain

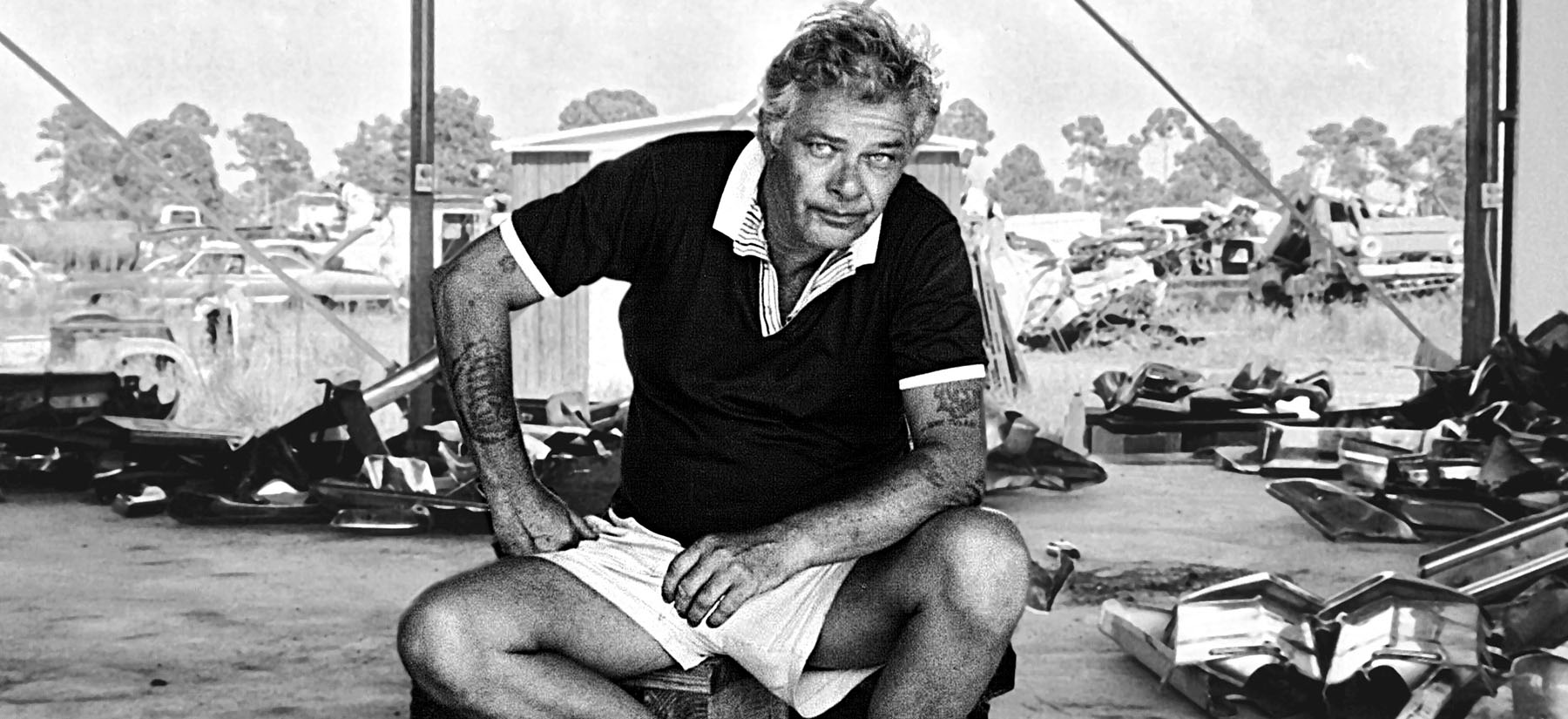

John Chamberlain (1927 – 2011) was a quintessentially American artist, channeling the innovative power of the postwar years into a relentlessly inventive practice spanning six decades. He first achieved renown for sculptures made in the late 1950s through 1960s from automobile parts – these were path-breaking works that effectively transformed the gestural energy of Abstract Expressionist painting into three dimensions. Chamberlain’s compositions of twisted, crushed, and forged metal also bridged the divide between Process Art and Minimalism, drawing tenets of both into a new kinship.

Embodying the inimitable energy of John Chamberlain’s sculpture, the sky blue, orange, bubble- gum and hot pink dominated ‘P.H.I.P’ (1979) evokes the influence of Abstract Expressionism as much as it reflects artist’s sense of innovation, liberation, poetic sensibility and legendary sense of humour.

P.H.I.P

A self-described collagist, Chamberlain was influenced early on by the compilation and welding methods of modernist sculptor David Smith, the spatial dynamism of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture and the expressionist gestures of Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning. Ultimately drawn to the ‘sustained presence’ of sculpture in the round, Chamberlain’s interest in spatial dynamics led him to develop a three-dimensional form of Abstract Expressionism, wherein the energetic coloured surfaces of de Kooning’s paintings manifest in metal. [1]

Pushing the boundaries of abstraction, in 1974, Chamberlain began a series of works made from compacted oil drums, which he referred to as ‘Sockets’, and double drums compressed together, which he referred to as ‘Kisses’—lending them a sexualized, anthropomorphic quality that corresponds to the artist’s notion of fluidity and fit. Although these works demonstrate the artist’s ingenuity and clearly subvert traditional notions of art, each eccentric fold and delicate crease of his barrels softens industrial indices, drawing art historical connections to the sculptural prowess of the Old Masters and Albrecht Dürer’s ‘Kissenstudien’ (Six Studies of Pillows) (1493). Occasionally, Chamberlain would give these works special titles, such as ‘P.H.I.P’, which also exemplifies his later method—as of 1974—of painting his metal parts prior to assembling them. The dynamism of ‘P.H.I.P’ represents the evolution of his idiom, relating to earlier works such as ‘Royal Ventor’ (1967), compacted boxes of galvanized steel that he had fabricated in enlarged proportions of cigarette boxes—inspired by his habit of crushing empty packs. The oil drums were produced after what Chamberlain described as a ‘seven-year hiatus’ during which time he explored new materials—namely foam, aluminium and synthetic polymer. [2] Spurred, perhaps, by his reengagement with car metal in 1972, Chamberlain produced twenty oil drum sculptures between 1974 and 1979, further extending the ‘Socket’ and ‘Kisses’ series in a group of ten miniatures comprising painted coffee cans, as well as an edition of thirty miniature reproductions published by Edition der Galerie Heiner Freidrich, Munich, in 1978. [3] Although this development represents one of the few edition projects in Chamberlain’s oeuvre, his pivot from large scale drums to cans articulates the underlying attitude of his practice that reverberates through his earlier galvanized steel boxes and cigarette packs: ‘if the scale is dealt with then the size has nothing to do with it’. [4] As noted by curator Susan Davidson, Chamberlain’s ability to work at any size was one of his greatest achievements and the variety of scale that he uses can often be related back to aspects of the body: the grip of a fist, an arm span, a person’s height. Through this, we find the cohesive attitude of his work, where ‘something as small as a top could have the same authority and the same expression as some of his large sculptures’. [5]

[1] John Chamberlain quoted in Michael Auping, ‘John Chamberlain: Reliefs 1960-1982’, Sarasota FL: The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, 1982, p. 9. [2] Susan Davidson, ‘A sea of Foam, an Ocean of Metal’, in ‘John Chamberlain: Choices, New York NY: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2012, p. 25. [3] Julie Sylvester, 'John Chamberlain. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Sculpture 1954-1985', New York NY: Hudson Hill Press & Los Angeles CA: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1986, p. 141. [4] John Chamberlain quoted in ‘Excerpts from a Conversation Between Elizabeth C. Baker, John Chamberlain, Don Judd, and Diane Waldman’, in Diane Waldman, ‘John Chamberlain: A Retrospective Exhibition’, New York NY: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1971, p. 18. [5] Chamberlain was known to delight fellow patrons at the famed Cedar Tavern by casually crushing cigarette packs into intricate sculpture. Susan Davidson in ‘John Chamberlain: Choices, An Audio Guide’, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, https://www.guggenheim.org/exhibition/john-chamberlain- choices.

Studio Visit: John Chamberlain talks to Michael Auping

This never-before-seen archival footage of American artist John Chamberlain is from a short film recorded over two days in South Florida by two local film-makers. These interviews and conversations culminated in the exhibition and catalog organized by Michael Auping, ‘John Chamberlain: Reliefs 1960-1983’.